It’s easy to feel a lack of control around pricing educational products. Competitor prices, demands from customers, and the presence of free products in the market are among the many factors that can make you feel you need to lower price.

At the same time, pricing is the most powerful lever available for managing net revenue. As I’ve noted before, a one percent increase in price results on average, in an 11 percent increase profit – significantly more than an equivalent increase in sales volume or decrease in costs.

On the downside, lower price by X percent, and you will need to increase volume by 2X percent to make up for it.

Bottom line: maintaining control over price is one of the most important things you can do for managing the health of your education business. Two essential factors can help you keep control of pricing educational products: differentiation and variation.

Differentiation

Michael Porter, arguably the leading figure in modern business strategy, made the argument many years ago that there are essentially two ways to compete effectively in any market: through having the lowest prices or through being different from the competition.

In most cases, being able to compete on price requires high sales volume and an ability to price below the competitors for a sustained period, as needed. Think Walmart or Amazon. I run across very few organizations that fit that profile. Differentiation is almost always the better choice.

So how can you differentiate when pricing educational products? Here’s a basic process:

1. Identify ultimate outcomes

First, invest time and thought into identifying the ultimate outcomes that learners seek from specific educational experiences (e.g., your annual conference) or categories of experiences (e.g., Webinars) you offer. No doubt they are seeking knowledge, skills, and possibly some form of credit (e.g., CE, CPE, CME), but why? Career advancement? Increased confidence? Job security? An edge in the job market? Prestige? The value of these ultimate outcomes is much higher that the value of knowledge, skills, or credit in isolation.

As I’ll discuss in the next post in this series, the ultimate value your learners seek will vary from person to person and from time to time, but there is probably a relatively stable set of motivations around which your baseline product can be developed. This is an area in which I find input from committee members and seasoned staff (from across the organization) can be of particular value. Get people to really dig deep to discover what really drives them to participate in your education programs.

2. Identify value signals

Next, identify the value “signals” in your market – signs that point toward the ultimate value you aim to create with your learners. Make as objective an assessment as you can of what drives value perception for the products or categories of products in your portfolio. To do this, you are going to want to:

- Get input from your internal experts – staff and volunteers

- Get perspectives from a solid sampling of your most ideal members/customers

- Take a hard look at what your most successful competitors are doing. On what value signals do they seem to place the most emphasis?

Compare the input from each of these sources – and, of course, apply your own judgment – to create a list of the signals that prospects seem to consider in seeking out and verifying the value you aim to deliver. Some typical signals for educational value might include:

- Subject matter expert (SME) reputation

- Access to SME

- Access to Peers

- Practice/Application Opportunities

- Credit Availability

- Supporting Materials Provided

- Proof of Demonstrable Improvement

- Related Costs (e.g., travel)

- Venue (for live events)

That’s not an exhaustive list, of course, but you get the idea.

3. Plot it out

As you go through these steps, try to assess how strong the value perception of each of these signals is on a scale from 1 to 10. In other words, how high is the value placed on each element in the market? Verify these rankings in discussions with staff, volunteers, and customers.

Then consider how well your organization delivers on each of the signals. Are you focusing too many resources on less important elements? Do you excel in at least a few of the most important elements? Where are you lagging?

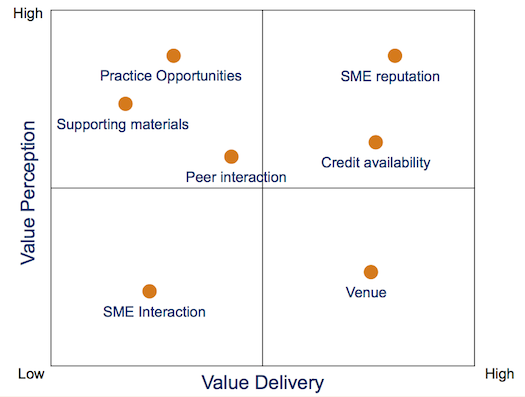

Finally, to make the exercise more powerful and easier to circulate for feedback, plot out the highest ranking markers on a simple double axis chart like the one pictured here – what we call your Product Value Profile.

How many of your value signals fall in the upper right quadrant – a place where value is perceived as high and you are effectively delivering on that value. (A good place to be!) What about the upper left? These are important, but you are not delivering on them as well. Or, look at the bottom right – not so important, but you are delivering well, and thus may be investing more than you should in these elements.

If you were to create a similar double axis charts for each of your key competitors and overlay them on your chart, how would you compare? How different do you look? What could you shift to make your products stand out more in the market?

This might mean investing more in areas where you are already strong in delivering value. It may also mean deciding to ignore or deemphasize other areas because you don’t feel the resource commitment is worth it.

The goal is not to shift everything into the upper right – that’s usually impractical. The goal is to identify very high value items that you do (or can) deliver on better than the competition and focus on getting those as high as possible in the upper right quadrant. Ultimately, you want a value profile that is as attractive as possible while clearly standing out from the profiles of you key competitors.

4. Identify new sources of value

The Product Value Profile can help sharpen your insights into how your products stand out in the market and provide a basis for pricing educational products that is different from the rest of the competitive pack.

But definitely don’t stop there.

Consider also how you might create value that the competition simply does not offer. Particularly value that is tied tightly to the ultimate outcomes your learners are seeking. This is the essence of Blue Ocean Strategy, a concept I covered in detail in a recent series of posts titled 6 Paths for Leading You Education Business to Blue Ocean.

I strongly encourage you to read this series and consider how the concepts it covers might apply to your products. Whether or not you are able to carve out a bona fide Blue Ocean, the approaches covered can help significantly with improving your overall Product Value Profile and putting you in much greater control of your pricing.

There’s plenty more to be said about differentiation, but having a basic process for determining and managing differentiation – like the Product Value Profile – is a good initial step. In the next part of this series, we’ll take a look at segmentation as a another key tool for setting and managing price.

In the meantime, what are your questions about differentiation or about pricing educational products, in general? How have you used differentiation more – or less – effectively to maintain a strong price position in your market? Please comment and share.

Jeff

P.S. Here’s a very relevant post I came across from Seth Godin: Understanding Marginal Cost. As Seth rightly explains, in undifferentiated markets there tends to be a rush to marginal costs in pricing, and –

The only defense against this race to marginal cost is to have a product that is differentiated, that has no substitute, that is worth asking for by name.

Leave a Reply