Note: We re-aired this episode interview in December 2023. For the most recent version, with more detailed show notes and a transcript, see “Redux: The Art and Science of Effective Feedback.”

It’s not unusual to be asked for feedback by a colleague or friend. And, likewise, it’s not unusual to be offered unsolicited feedback, whether from a boss, colleague, or friend.

But giving—and receiving—feedback is arguably harder than most people think. It’s an art and a science. And it’s exceedingly important that learning professionals take the time to learn that art and science because of the critical role that feedback plays in learning.

In this episode of the Leading Learning Podcast, Celisa and Jeff delve in to the topic of feedback, including how to effectively give and receive it, common misconceptions around it, and the tremendous impact it can have on learning.

To tune in, just click below. To make sure you catch all of the future episodes, be sure to subscribe by RSS, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher Radio, iHeartRadio, PodBean, or any podcatcher service you may use (e.g., Overcast). And, if you like the podcast, be sure to give it a tweet!

Listen to the Show

Read the Show Notes

[00:18] – A preview of what will be covered in this episode where Jeff and Celisa explore the topic of feedback.

Note that in episode 203 – 7 Metalearning Moves to Empower Lifelong Learning– feedback was one of the important metalearning moves we covered so we wanted to dedicate more time to the topic.

Reflection Questions

[01:37] – You might consider the reflections questions below on your own after listening to an episode, and/or you might pull the team together, using part or all of the podcast episode for a group discussion.

- Think about the feedback you offer your learners. As you listen to our conversation, think about whether the feedback you offer is consistent with what’s known about how to foster learning.

- As we talk about the many different types of feedback, think about which ones you do and don’t use. After the episode think about whether it might be beneficial to change the types of feedback you offer. Would codifying approaches to different types of feedback be valuable?

Defining Feedback

[02:21] – Let’s start by defining feedback. According to Merriam-Webster, feedback is “the transmission of evaluative or corrective information about an action, event, or process to the original or controlling source.” Feedback is also “the information so transmitted.”

The evaluative or corrective nature is key. In the context of learning, that’s going to be evaluation or correction about skills or knowledge being learned, and the original source is going to be the learner herself.

But feedback has two sides. There’s giving feedback, and there’s receiving feedback.

We’re going to spend most of our time today on giving feedback—because that’s a responsibility and a privilege that learning businesses usually fulfill. But we’ll start by touching briefly on asking for feedback because as lifelong learners that side of the feedback skill set is worth working on too.

Asking for Feedback

[04:15] – Celisa shares about a poetry workshop she attended where the poets could specifically ask what type of feedback they were looking for (e.g., regarding the ending of the poem).

And Jeff talks about his experience working at Heroic Public Speaking (HPS) and how you can only offer feedback if the person specifically requests it. So you need to ask for the specific feedback that’s really going to make you better.

Asking for feedback or—perhaps even more relevant for learning businesses—letting or encouraging learners to ask for feedback often works best at either end of the learner journey—for the novice or for the approaching-expert learner.

For the novice, there’s often so much corrective feedback to give that it can overwhelm the learner, so letting the learner pick where those giving feedback focus can help limit the sheer volume of feedback to a manageable amount.

For example, a novice tennis player has a bad backhand, a weak forehand, anda serve that’s unreliable. But that’s a lot to work on, so the player might say she wants to focus on serve and asks for pointers on that.

And, for the approaching-expert learner, asking for feedback on a particular area can increase the odds that the feedback prompts action or elicits change. An advanced tennis player may simply not care about improving her serve. Maybe she’s a savvy enough player that she knows she can consistently put the ball in play, and that’s good enough for her. But she might feel she really needs to put her time and energy into improving her backhand, for example.

So if you’re going to ask for feedback—or create learning experiences, like the HPS workshops and the poetry workshops we mentioned—where you’re going to encourage learners to ask for the feedback they need or want, it’s a good idea to provide an example to model.

And whoever is hearing the feedback—you or another learner—or, in the case of a structured learning experience, the instructor or facilitator, needs to be ready to redirect feedback givers if need. Or, if that doesn’t work, know you or the other learner can ignore the feedback if needed.

Feedback, like any learning, is always up to the receiver—even really good feedback can only be conveyed (“transmitted” to use the word from our definition), but won’t necessarily be internalized, adopted, put to use—it’s always up to the learner to apply it or not.

Sponsor: Community Brands

[09:35] – If you’re looking for expert help with your learning business, check out our sponsor for this quarter.

Community Brands provides a suite of cloud-based software for organizations to engage and grow relationships with the individuals they serve, including association management software, learning management software, job board software, and event management software. Community Brands’ award-winning Crowd Wisdom learning platform is among the world’s best LMSes for corporate extended enterprise and is a leading LMS for association-driven professional education programs. Award-winning Freestone, Community Brands’ live event learning platform, is a leading platform for live learning event capture, Webinars, Webcasts, and on-demand streaming.

Giving Feedback

[10:27] – And now to the other side of the road: giving feedback.

Giving feedback is a responsibility and a privilege and—we’ll say it—a potential liability for learning businesses. Liability because, while feedback is so critical to learning, it’s hard to do well.

Feedback should be focused on improved performance—in the case of learning businesses, opportunities for feedback should focus on improving the learning, so that the learner better understands the skills and information being taught and is better able to apply those skills and information. The corrective and evaluative nature of feedback needs to keep that goal of improved performance in mind.

And keeping that goal of improved learner performance in mind, it’s pretty easy to see that, yes, there’s such a thing as unnecessary feedback, gratuitous feedback, even bad feedback. Anything that undermines improved learner performance is counterproductive. And it’s not hard to imagine—or perhaps even remember—examples of feedback gone awry.

Feedback about how distracting someone’s facial expressions are while speaking turns into not more pleasant facial expressions but results in that person not speaking up as much, not presenting at events, and so on.

So we have to keep the goal of improved learner performance in mind. In addition, feedback should take the learner and the situation into account.

Individual learners when possible; if not, then types of learners (e.g., novice vs. expert or native English speakers vs. non-native English speakers). Knowing who’s receiving the feedback allows us to structure it in a way most likely to achieve that goal of improved performance. More expert learners are more likely to be able to process nuanced feedback and feedback on a variety of aspects.

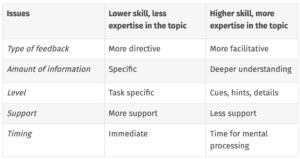

Novice learners may be overwhelmed by too much feedback and may need help understanding what to do with feedback—for example, a recommendation to a novice public speaker to be more engaging won’t be as meaningful as that recommendation coupled with some examples of how to be more engaging—by using stories or strategic movement on the stage. We need to be more directive with novices, and more facilitative in our feedback to more experienced learners.

See Mastering Deeper Learning, Part 2: Feedback by Dr. Patti Shank for a good summary of how to handle feedback differently at the different ends of the skill and expertise continuum.

(Table 3.2 from https://elearningindustry.com/mastering-deeper-learning-part-2-feedback)

It’s also important to keep in mind what the feedback is on. Feedback on a knowable, reproducible task/procedure (e.g., giving an injection) will be different than feedback on a more open-ended topic (e.g., being a more strategic thinker). With the knowable tasks, the corrective side of feedback factors in—there’s a right way to give an injection, and you want to make sure learners get it.

With more open-ended topics, the feedback will be more evaluative than corrective. There’s not a single right way to be a strategic thinker—but there are some things you can say or do that might point a learner in the right direction—hints, cues, details that might get her thinking or experimenting.

Dimensions/Types of Feedback

[14:35] – In addition to being aware of the individuals and the situations the feedback pertains to, there are also various dimensions of feedback. From formal (think assessments—e.g., a certification exam) to informal (“insignificant” day-to-day exchanges).

There’s also a feedback spectrum that runs from formative to summative.

And there’s solicited vs. unsolicited feedback, and shades of gray in between those two extremes.

And there’s who’s giving the feedback. Is it coming from a teacher or an expert? Is it coming from peers? Peers with more experience or less? Or is the feedback coming from the learner herself? Maybe through reflection or other activities and experimentation.

And of course there’s the spirit of the feedback. Is it positive/constructive/supportive? Or is remedial/negative?

Is it direct (written or spoken)? Or is it implicit (body language?) Is it straightforward and clear or couched beyond parseability to preserve the appearance of politesse?

With so many variables to feedback, it’s easy to see how quickly it becomes complicated and why some folks have pushed back on the idea of feedback ever being valuable.

“The Feedback Fallacy”

[16:04] – In a recent Harvard Business Review article titled “The Feedback Fallacy”, the authors, Marcus Buckingham and Ashley Goodall write:

Feedback is about telling people what we think of their performance and how they should do it better—whether they’re giving an effective presentation, leading a team, or creating a strategy. And on that, the research is clear: Telling people what we think of their performance doesn’t help them thrive and excel, and telling people how we think they should improve actually hinders learning.

And those authors go on to point out what they see as three fallacies around feedback:

- First, “that other people are more aware than you are of your weaknesses, and that the best way to help you, therefore, is for them to show you what you cannot see for yourself.”

- Second, “that the process of learning is like filling up an empty vessel: You lack certain abilities you need to acquire, so your colleagues should teach them to you.”

- And third “that great performance is universal, analyzable, and describable, and that once defined, it can be transferred from one person to another, regardless of who each individual is. Hence you can, with feedback about what excellence looks like, understand where you fall short of this ideal and then strive to remedy your shortcomings.”

But each of those points is flawed—others don’t always see us more clearly or understand what we need to do and by sharing what they see and what they think we need to do, we may actually move farther away from doing something well. We’ll note that this is truer for higher-order learning and for learning that aims not just for competence but mastery, or in the language of the HBR authors, excellence—for giving an injection properly, others may well be able to helps learners do that better.

We should also note there is some basic neuroscience behind what the authors of this HBR article claim around feedback:

For example, their studies show that, “in the brains of the students asked about what they needed to correct, the sympathetic nervous system lit up. This is the “fight or flight” system, which mutes the other parts of the brain and allows us to focus only on the information most necessary to survive. Your brain responds to critical feedback as a threat and narrows its activity.”

On the flipside, if we’re actually able to highlight for somebody what’s working in what they’re doing/learning, that can actually stimulate the parasympathetic nervous system which is much more productive and can lead to the neurogenesis/growth of brain cells. So the authors’ view is that learning really rests on our grasp of what we’re doing well, not on what we’re doing poorly—and definitely not on someone else’s sense of what we’re doing poorly.

Also, we learn the most when someone else pays attention to what’s working within us and asks us to cultivate that intelligently—that’s the best kind of feedback. So, for example, if you see somebody doing something that’s really working, stop and highlight that and recognize that to point out what excellence looks like. If you do that, you’re offering her a chance to gain some insight, you’re highlighting a pattern that’s already there within her so she can recognize it, anchor it, recreate it, refine it, etc.

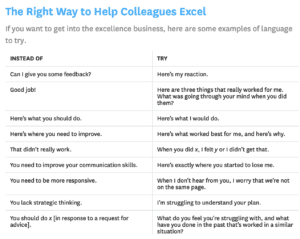

Below is a chart from the HBR article with some language substitutions and some example situations of how to give feedback [present, past, future]. It’s less in learning events/experiences and more in the informal learning context, but much of it can be generalized to feedback you might give in a formal learning context:

This also dovetails really well with Carol Dweck in her great book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, because she spends a good bit of time talking about feedback and how feedback can foster or inhibit a growth mindset. Feedback should stress and praise the learners’ effort and process vs. judging learners’ talent or intelligence.

Praising their effort and process will put people in a growth mindset. But praising learners’ intelligence (certainly positive feedback!) can trigger the fixed mindset, because that feedback is a label. And even a positive label—calling someone “smart”—equates that person with their achievement or performance.

To prompt a growth mindset, you want to praise effort or the way of thinking—saying, “That was a smart way to think about that problem” is different than saying, “You’re smart.”

See our related episode about mindset, Maximizing Learning with Mindset.

Be an Avatar

[22:27] – As we’re beginning to wrap up, we’ll note that as with so much we do as learning businesses it’s really important and meaningful to not only talk the talk but walk the walk, to be the avatars for the kind of behavior we want and expect from our learners.

So while it’s a different kind of feedback, asking for feedback from learners, asking them to complete post-course evaluations, is a way of modeling the importance of feedback. It shows we’re open to feedback and hopefully that we’re open to make changes and improve based on that feedback.

[23:19] – Wrap-Up

Reflection Questions

- What feedback are you offering your learners? Is the feedback offered consistent with what we know about how to promote learning?

- Would you benefit from revisiting and perhaps codifying the types of feedback you offer?

If you are getting value from the Leading Learning podcast, be sure to subscribe by RSS, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher Radio, iHeartRadio, PodBean, or any podcatcher service you may use (e.g., Overcast).

We’d also appreciate if you give us a rating on Apple Podcasts by going to https://www.leadinglearning.com/apple. We personally appreciate your rating and review, but more importantly reviews and ratings play a big role in helping the podcast show up when people search for content on leading a learning business.

And we would be grateful if you check out our sponsor for this quarter. Find out more about Community Brands.

Finally, consider following us and sharing the good word about Leading Learning. You can find us on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn. We also encourage you to use the hashtag #leadinglearning on each of those channels. However you do it, please do follow us and help spread the word about Leading Learning.

See Also:

- Redux: The Art and Science of Effective Feedback

- 7 Metalearning Moves to Empower Lifelong Learning

- Maximizing Learning with Mindset

- A Why-To and How-To on Hot Seats, AKA Collaborative Coaching

Never Stop Learning with Dr. Bradley Staats

Never Stop Learning with Dr. Bradley Staats

Leave a Reply