I first posed this question in a post published in 2014. At the time, I framed it as “not such a crazy question” given the growing criticism of higher education as well as the emergence of myriad options for self-directed learning and the rise of alternative forms of credentialing.

Roll forward eight years, and the questions seems even less if crazy – if crazy at all.

For the most part, higher education – and, in particular, undergraduate education – has failed to repair or reform (much less transform) itself. Tuition costs remain high – too high for many adult learners – while the results they underwrite are arguably not what they should be. While it is still true that college graduates on average fare better economically than non-graduates, there are nuances buried in the averages that often get overlooked.

First, most of the economic gain comes from actually graduating – it is the degree, not the education that creates the most value in employment markets. College often amounts to a very resource intensive version of what is called “job market signaling” in economic circles. If you shell out the money for multiple years of college but don’t actually finish, you will likely be sorely disappointed by the economic returns.

Second, there is a credible case – as put forward by Bryan Caplan in The Case Against Education – that only certain types of students realize the economic benefits of college. For many, it is a bad choice from the get-go, but as Blakes Boles (drawing on Peter Thiel) argues in Why Are You Still Sending Your Kids to School, we have made higher education into a sort of secular religion against which is very difficult to transgress. (Donald Clark also offers a compelling comparison between the medieval Catholic church pre-Luther and our current higher education system.)

Even if we lay these (and other) economic considerations aside, everything we know about how learning happens best – spaced over time, with continued effort and progressive practice, ideally in a context as similar as possible to the one where the learning will actually be applied – and everything we are seeing in the current world of work (not to mention the world more generally) suggests that the de-contextualized “massed learning” represented by the traditional undergraduate degree is not the best approach to preparing most of us for work and life. As the authors of a 2019 Harvard Business Review article put it:

In an age of ubiquitous disruption and unpredictable job evolution, it is hard to argue that the knowledge acquisition historically associated with a university degree is still relevant.

There is, of course, the argument that college in its traditional, on-campus form is not really about “knowledge acquisition” – it is about the experience. It is about providing a place where young people can transition into adult life, with the opportunity to try new things and build new relationships in a relatively low risk environment. Like job market signaling, this is a very expensive, resource-intensive approach to a problem – if it actually is one – that could be solved in other ways – like, say, through experiences readily available in life itself. And it’s an approach historically available only to the privileged or those willing to assume the risk of significant debt. It seems particularly out of tune with our current cultural moment.

All of the above are issues that have existed for years, but they are now compounded by the looming financial crisis sparked by COVID-19. By some reports, U.S. colleges and universities were already experiencing an enrollment decline over the past decade. Now they stand to lose billions of dollars not only from a sharp decline in enrollments – both domestically and internationally – but also from the market declines, decreases in donor funding, and government budget cuts that are likely to accompany an economic downturn. There are already clear signs that enrollments have dropped substantially from pre-COVID levels and dropout rates are increasing.

These declines will be accompanied by a need to invest significantly in online capacity for institution that want to survive. Many won’t survive the shift, though, and it may be only the biggest brands – Harvard, Stanford, Oxford – that truly manage to thrive in the new frontier of higher education. It’s difficult not to believe that some version of the bleak future NYU professor Scott Galloway paints – in which big tech and big university brands unite – will come to pass.

The Role Associations Can Play

Most likely some form of college will persist for many years to come, but whatever form it takes, it seems more than reasonable to ask at this point whether it couldn’t be replaced with something more in line with our current world.

Which brings us back to the title question: Could associations replace college?

There are good reasons to think they could in many instances.

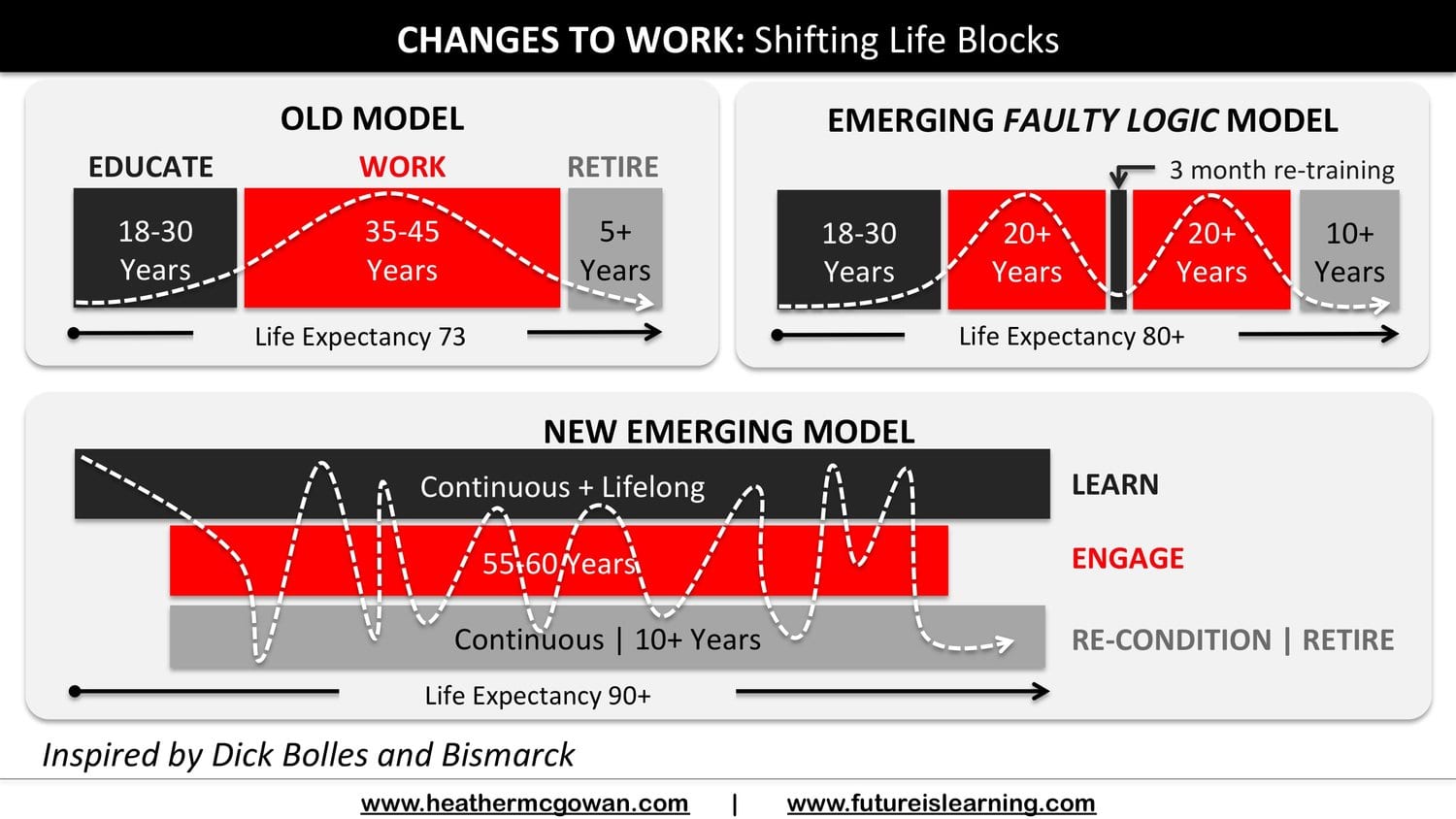

Associations already have a long history of providing career-related education to the people in the industries and professions they serve, making it possible for individuals to continually update and add to their knowledge and skills. As Heather McGowan has illustrated so concisely, this is precisely what is needed to navigate work in our current world.

We need the ability to move in and out of formal educational experiences while also having access to resources that support our learning in the flow of work. “Higher” education makes much more sense not as a single, large chunk of time, but as many smaller chunks and connections spaced out over time.

While the educational experiences offered by associations are usually characterized as “continuing education” – positioning them in relation to higher education – many associations already do offer learning experiences that are foundational to employment. It is not difficult to imagine significant expansion of programs – bootcamps, institutes, and the like – that help onboard people into careers, establishing an initial base from which additional learning will flow and evolve.

Associations also have a long history of providing various forms of credentialing, from certificates to high stakes certifications, that are themselves a form of the “job market signaling” in which so much of the value of higher education degrees resides. In my experience, many have not fully appreciated the signaling aspect of their credentials – meaning they have not put sufficient effort into establishing their value with employers – but again, it is not difficult to envision that changing. (And, of course, for many associations, this is already a booming area of business.)

Associations are also in the unique position of representing members throughout whatever period of time they remain in the field or industry they serve – which in many instances means throughout their entire career – even as they change jobs and employers. In other words, they are in the career business.

What’s more, by nature of their day-to-day activities and their relationships with members and employers, associations are uniquely positioned to understand the knowledge and capabilities most needed now and in the future within their particular field or industry. It’s become very trendy in learning and development circles to talk about a “culture of learning” and “learning ecosystems.” Because they transcend specific employers, associations are arguably in the best position to be the primary facilitators of the learning culture and ecosystems within a given profession. They are in a better position than just about any other entity to lead learning.

Finally, associations are, by their very nature, networks and – in the best cases – learning communities, ones that blend education, career, and personal identity to a degree unmatched by any other institution. Arguably, one of the most valuable intangible aspects of the traditional college experience has been the relationships students develop during their years of study. These relationships, along with the shared sense of identity that makes it possible for them to reach out even to other graduates who they do not know personally, can be of significant help in navigating the years of life and career that follow college. While associations may never offer the level of bonding possible in a four-to-five-year on-campus experience, it is again not difficult to see how specialized programming can help foster significant long-term relationships among members.

And, of course, associations already offer a shared sense of identity to members along with myriad opportunities for connecting and re-connecting throughout a career – precisely the type of support structure that is valuable for learning in the flow of work and learning in the flow of career. The strongest and most useful learning emerges out of connection, community, and a shared sense of identity over time.

Each of the points above is compelling separately. Combined, they offer a portrait of an institution that is primed to support the future of work and the future of learning.

What Does the Shift Require?

The reality is that, for the most part, associations already play the role I describe above. They are a key component of what I have characterized elsewhere as the “third sector of education,” the massive, but generally overlooked and underappreciated network of support for adult lifelong learners that has become increasingly critical in our increasingly complex, chaotic, and fast-changing world.

As I’ve also pointed out, association leaders have also been conspicuously absent in most of the public debate around addressing the need for lifelong learning. If associations are to be seen as a viable alternative to college, that will need to change, but other key changes will also be needed.

Re-framing Membership

While there have been a handful influential books and articles in the past several years that have questioned the relevance of associations and the future of membership, these have been primarily good for driving business for consultants and less helpful for accurately assessing the state of associations. For the majority of associations, membership has either increased or held steady in recent years. (Source: Marketing General)

Associations aside, membership as a business model is booming, as Robbie Kellman Baxter has convincingly illustrated. With the right leadership and positioning, there are clear upsides to embracing what Baxter characterizes as “the forever transaction.”

Traditional association membership has been primarily about identification with a group – a sense of professional “belonging” – and – for purposes of bargaining and advocacy – strength in numbers. These are basic human needs and, as such, will remain reasons for joining an association, but there is an opportunity in our current environment to forefront the value of membership as a conduit for learning, as a source of guidance and clarity in maintaining and developing the knowledge needed throughout a career.

In my experience, there are a growing number of learning leaders at associations thinking in this way, but few have implemented a vision that is visible to their members and prospective members. The average association value proposition still tends to be “pay us money so that you can belong and get discounts.” From this perspective, members are really more like customers – and there has been a long-term shift toward associations treating them this way.

This difference – customer vs. member – is subtle, but critical to recognize because of the expectations implicit in each.

A customer is primarily seeking value for herself in exchange for money. While a member also seeks personal value, she also buys into – literally and figuratively – a set of values and a vision (at least if the association is doing its job). When the customer mentality seeps into association operations, it changes the nature of member relationships. It becomes easy to be focused more on the needs of individual members (really, customers) than the greater purpose for which membership was originally (at least in theory) seen as a conduit. Transactions trump relationships, leading to a lot of “checkbook” members.

It’s not an academic point: Organizations that really aim to lead learning in the industries and professions they serve need members – not just customers – who are bought into that vision. This goes well beyond the Netflix or Amazon Prime conception of membership, and it is critical, in my opinion, to real leadership in the third sector.

Embracing Learning as a Process

Core to the idea that associations have a special role to play in lifelong learning is the understanding that learning is a process that takes place over time. Often a long time. Even a four-to-five-year span of time, particularly one that is often a collection of disjointed experiences, is nowhere near sufficient.

But associations themselves are currently too focused on learning as an event rather than a process.

Indeed, the annual event – thrown into turmoil for most organizations by COVID-19 – is often the main, if not only, focused effort for providing educational support to members. Members convene, sit through multiple general and breakout sessions over multiple days, and then forget the vast majority of what they have heard within days of leaving the event.

The same is true of the catalog of seminars and online courses that many organizations offer. These are one-off educational events, based more on a single transaction than an ongoing relationship with the learner.

That will need to change for the true value of associations as lifelong learning facilitators to be realized. To return to the idea of culture and ecosystems, associations need to view each event as just one touch point in the learner’s journey and focus both on helping the individual learner map that journey and on developing the culture and ecosystem in which the learning is supported.

Forging Productive Partnerships

While I have been critical of higher education in this article, the shift I’m describing cannot be achieved by associations alone. Academia is an important partner. There are still plenty of instances, of course, where the concentrated acquisition of technical skills is needed before entry into a profession, and a two- or four-year college may remain the most effective option for this type of training and education in many instances. (Though, to be honest, it is not difficult to imagine larger associations acquiring all or parts of institutions that address this need in their particular field.) Even so, there is room for significantly tighter academic-association collaboration than exists in most fields and industries around curriculum development and onboarding into the relevant career paths.

And, of course, college is not graduate school and it does not represent the research role of universities – again, both areas in which there is greater opportunity for academic-association collaboration.

Employers, too, are a target for increased collaboration. While many associations do maintain employer relationships, we have found that there is very often a disconnect between the educational offerings and credentials associations develop and what employers actually value and need. And, in many instances, employers – and particularly decision makers at employers – are simply unaware of the educational options that associations in their field can or do offer.

One obvious starting point for forging greater connection among employers, academia, and associations would be for associations to get involved in the Open Skills Network, and initiative that already connects employers and higher education but that has little, if any, association presence.

Last but not least, everything I have covered here requires a re-thinking of the relationship between associations and the subject matter experts (SMEs) – often volunteers – who create and deliver much of association education. Our experience suggests that the bar will need to be raised significantly for the teaching and facilitation skills required of SMEs. This is part of the development of the “culture” that has already suggested, and it is one that will require more sophisticated recruitment efforts, coordinated training efforts, and potentially payment (or higher payment) of SMEs that make the cut.

The Need for Leadership

While the foundation for everything I have described here is already well in place, there is little reason to believe it will just “happen.”

Most of it goes against how things have been done in the past at associations and how most associations – and the leaders of their learning businesses – seem to conceive of themselves.

It goes against how education departments tend to be viewed at many associations – often as lower in the pecking order to events and membership – and the level of resources allocated to these departments in spite of their revenue-generating role.

And, of course, academia isn’t sitting still. While there may be issues with the traditional college degree programs, continuing education is rapidly evolving to a new level at many institutions. In combination with alumni programs and the types of relationships with employers I have already suggested, they are well positioned themselves to play a leading role – perhaps the leading role – in the third sector.

None of which is to suggest that this is a competition. The reality is that, if academic continuing education and associations were both to emerge as clear leaders of a vibrant third sector – ideally with strong collaboration between them – that would be a win for everyone evolved.

But for associations, that currently requires a surge in vision and leadership, one that could transform how we think about the traditional path from secondary education into career.

It’s a powerful idea. And it’s not so crazy.

Jeff

Title photo credit: https://pixabay.com/photos/university-lecture-campus-education-105709/

Related Leading Learning Posts

Related External Reading

- Is This the End of College as We Know It?

- Earning, Learning and Closing Skills Gaps With Apprenticeships

- More colleges project tuition revenue will decline: report

- College isn’t the solution for the racial wealth gap. It’s part of the problem.

- College degrees may no longer be the great equalizer: study

The Indispensable Community with Richard Millington

The Indispensable Community with Richard Millington

Universities with large reserves will buy association content and credentials and drive them through their tech company partners platforms. Universities will have to abandon their historic requirements for faculty membership and FTE’s.

Thanks for commenting, Glenn. I definitely agree that all of that is a possibility. – Jeff